NEW DELHI-The Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Gujarat state has implemented an “anti-conversion” law passed in 2003, increasing Christians’ fears that it will open the door to false accusations by Hindu extremists.India’s Freedom of Religion Acts, referred to as anti-conversion laws, are supposed to curb religious conversions made by “force,” “fraud” or “allurement.”But Christians and rights groups say that in reality the laws obstruct conversion generally, as Hindu nationalists invoke them to harass Christian workers with spurious arrests and incarcerations.Rules of implementation under the Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act of 2003 were framed on April 1, The Times of India reported, adding that those convicted of “forced” conversion could receive up to three years in jail.“From now on, anyone wishing to convert will have to tell the government why they were doing it and for how long they had been following the religion which they were renouncing, failing which, they will be declared offenders and prosecuted under criminal laws,” the daily reported on Saturday (April 26).

NEW DELHI-The Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Gujarat state has implemented an “anti-conversion” law passed in 2003, increasing Christians’ fears that it will open the door to false accusations by Hindu extremists.India’s Freedom of Religion Acts, referred to as anti-conversion laws, are supposed to curb religious conversions made by “force,” “fraud” or “allurement.”But Christians and rights groups say that in reality the laws obstruct conversion generally, as Hindu nationalists invoke them to harass Christian workers with spurious arrests and incarcerations.Rules of implementation under the Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act of 2003 were framed on April 1, The Times of India reported, adding that those convicted of “forced” conversion could receive up to three years in jail.“From now on, anyone wishing to convert will have to tell the government why they were doing it and for how long they had been following the religion which they were renouncing, failing which, they will be declared offenders and prosecuted under criminal laws,” the daily reported on Saturday (April 26).Social Impact

“There is absolutely no truth in the allegation that Christians use unfair means to convert the poor and Dalits to Christianity,” the Rev. Dr. Dominic Emmanuel, spokesman of the Delhi Catholic Archdiocese, told Compass.Besides numerous false complaints by Hindu nationalist groups against Christian workers under other states’ anti-conversion laws, the legislation has a negative social impact.“These anti-conversion laws have a negative social impact on Christians, as people try to ostracize the Christian community whose only purpose to them seems to be to convert, thereby belittling all the social work the community does for the masses,” Emmanuel said. “Christian workers are prevented from reaching out to the needy, who too will continue to suffer.”Emmanuel added that the legislation also had a bearing on the status of those who are “prevented to embrace Christianity, joining which they would break away from the caste hierarchy [in Hinduism] and be treated on equal status with other believers.”He noted that such legislation seems to leave many citizens with a false impression that conversion itself is illegal in the country; frequently intolerant Hindus accuse Christians merely of “conversion,” rather than “forced” or “fraudulent” conversion.Emmanuel added that the only purpose of anti-conversion rhetoric, which later gets translated into anti-conversion laws, is to “demonize the miniscule, peace-loving Christian community with an eye on consolidating the Hindu votes.”The BJP in Gujarat is infamous for persecuting religious minorities of Muslims and Christians. In 2002, Hindu nationalist groups killed more than 2,000 Muslims, as the BJP government reportedly looked on. In 1998, Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) extremists launched a series of attacks for more than 10 days in Gujarat’s Dangs district.According to the 2001 census, there are only 284,092 Christians in Gujarat, which has a total population of more than 50 million.

Conversion Made Difficult

The rules under the Gujarat law make it obligatory for clergy seeking to convert someone from one religion to another to obtain prior permission of the district magistrate in order to avoid police action.Clergy will be required to sign a detailed form providing personal information on the person whom she/he wishes to convert, whether the one to be converted is a minor, a member of Scheduled Caste (Dalit) or Tribe (aboriginal), her/his marital status, occupation and monthly income.“Anyone willing to convert will have to apply to the district magistrate a month before the rituals involved in conversion and give details on the place of conversion, time and reason,” noted The Times of India. “After getting converted, the person will have to obligatorily provide information within 10 days on the rites to the district magistrate, reason for conversion, the name of the priest who has carried out the ritual and full details of the persons who took part in the ceremony.”The district magistrate will have to send a quarterly report to the government listing the number of applications for prior permission, comparative statistics of the earlier quarter, reasons for granting or not granting permission, number of conversions and number of actions against offenders.Although Christians are now more apprehensive about their safety in Gujarat, the BJP’s move was not unexpected.The Gujarat government had taken up the legislation a month after revoking an amendment bill, the Gujarat Freedom of Religion (Amendment) Bill of 2006, which sought to make the law more stringent. The BJP revoked the amendment bill on March 10 in an apparent attempt to implement the 2003 version of the legislation that had remained dormant. (See Compass Direct News, “State Revokes ‘Anti-Conversion’ Amendment Bill,” March 11.)The Gujarat government repealed the amendment bill as Gujarat Gov. Nawal Kishore Sharma had refused to give his assent to it in July of last year, saying it “violated the right to religious freedom.” Following the governor’s move, the government on August 1 officially declared that it would reactivate the 2003 anti-conversion law, reported The Indian Express.The repealed amendment bill stipulated that people from the Jain and Buddhist faiths would be construed as denominations of Hindu religion – a provision that was opposed by leaders from the Jain and Buddhist communities, as even the government census distinguishes between Hinduism and the other two faiths.It also sought to exclude from the definition of “conversion” the renouncing of one denomination for another.

Hurdle in Rajasthan State

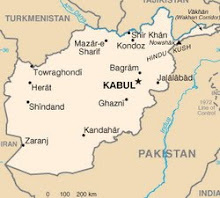

Anti-conversion laws are now in force in five states – Gujarat, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Himachal Pradesh, and they have been passed but are yet to be implemented in Arunachal Pradesh and Rajasthan states.In Rajasthan, the BJP government is facing a hurdle in implementing the new law it passed earlier this year – Gov. S.K. Singh refused to give his assent, so the party seeks to replace the Rajasthan Religious Freedom Bill 2006 with a newer version, reported The Statesman on April 20.“The Rajasthan Religious Freedom Bill 2008 was re-introduced and passed in the budget session with some amendments since its earlier draft was widely slammed as a draconian attempt by the BJP government to curb religious freedom in the state,” said the daily.The dormant law of Arunachal Pradesh is not likely to be implemented in near future, given that no attempts have been made in that direction since it was passed in 1978.The head of the National Commission for Minorities, Mohammad Shafi Qureshi, has said the panel will set up a committee to examine if anti-conversion laws in India throttle people’s freedom to practice any faith, reported Indo-Asian News Service on March 28.

Pending Legislation

The BJP also has introduced amendment bills to make existing anti-conversion laws more stringent in the states of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. But both bills are facing objections by their respective governors.Chhattisgarh Gov. Ekkadu Srinivasan Lakshmi Narsimhan raised objections to two provisions of the state amendment bill – obtaining permission from the district collector (administrative head) before any conversion, “and allowing people to return to Hinduism and not treating this as conversion,” reported news agency Press Trust of India on August 22, 2007. Gov. Narsimhan reportedly referred the bill to the state law department for assessment.Earlier, in June 2007, Attorney General of India Milon Banerji criticized the Madhya Pradesh state anti-conversion amendment bill passed by the BJP on July 21, 2006. Madhya Pradesh Gov. Balram Jakhar had sought Banerji’s opinion on the proposed amendment.The proposed amendment in Madhya Pradesh requires clergy and “prospective converts” to notify authorities of the intent to change religion one month before a “conversion ceremony.”In its current form, the Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act of 1968 requires that notice be sent to the district magistrate within seven days of conversion.

Maharashtra Law

A local Hindutva leader in Borivali area of the state capital of Maharashtra state, Mumbai, has demanded an anti-conversion law in the state – apparently under the same, increasingly mistaken notion that such legislation is designed to prevent conversion altogether.Swami Narendracharya, popularly known as Narendra Maharaj, was quoted yesterday (April 27) on the website of a private news channel, Zee News, as saying. “An anti-conversion law is needed ... Nobody should be converted, whatsoever be his religion.”“Re-conversion,” for Maharaj, is apparently a different matter. He claimed that he recently re-converted around 1,800 tribal Christians back to Hinduism, and that in total he has re-converted to Hinduism 42,220 people, mostly from tribal areas of Maharashtra and neighboring Gujarat state.

As in the days of Noah....

.bmp)

No comments:

Post a Comment