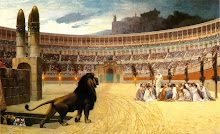

TEHRAN, IRAN-Illyas, 20, precariously straddles two worlds.At home with his family, he's a devout Christian who wears a silver cross around his neck, devotionally reads the Bible, and, on the Sabbath, hums hymns of praise to Jesus.Easter and Christmas are celebrated with homemade grape wine, even though alcohol is banned in Iran.Publicly, though, Illyas is a devout Muslim.Before leaving home to attend university classes, he removes the cross.He falsely tells his teachers about reading the Koran regularly since, he says, expressing fealty to Islam is necessary to land a good job in Iran.And he regularly goes to Friday prayers at Tehran University, where, if necessary, he joins in chants of Marg-bar Amrika (Death to America)-although he says that he doesn't hate America and, in fact, hopes to move there someday.Illyas and his mother and stepfather-for their safety, their family name cannot be revealed—had been Muslims (as are 98% of the nation's 66 million citizens).That changed a year ago, when they were drawn to a seductively passionate voice on a satellite TV channel imploring Iranians to embrace Christianity.On hearing the voice, Illyas's mother called the channel's hotline number. She prayed with the counselor on the phone, she says, making a personal commitment to Jesus as her savior.Later, Illyas and his stepfather did the same, as the counselor from California's Iran for Christ Ministries led them in prayer.The counselor was able to put Illyas in touch with some local Iranians—also discreet believers—who could provide a copy of the Bible. "We were looking for a faith that offered the reassurance of freedom,'' says Illyas, who asked to be interviewed in a public restaurant in Tehran instead of his house.Islam is the state religion of Iran, governing most aspects of life since the 1979 Islamic revolution. But, exasperated with the obsessive atmosphere of Islamic purity in Iran since the revolution and the subsequent curbing of social freedoms, Illyas says, his family felt compelled to look for other spiritual answers, even at considerable risk.Leaving Islam for another religion, or apostasy, has long invited reprisals from the Iranian government, forcing the likes of Illyas and his family into absolute secrecy, practicing their new beliefs only in the privacy of their home. In Iran, Christians are prohibited from seeking Muslim converts, although there has been tolerance for those who are born into Christian families.The government of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has introduced legislation before the Iranian Majlis that would mandate the death penalty for apostates from Islam, a sign that it will brook no proselytizing in the country. "Life for so-called apostates in Iran has never been easy, but it could become literally impossible if Iran passes this new draft penal code," says Joseph Grieboski, the president of the Institute on Religion and Public Policy in Washington. "For anyone who dares question the regime's religious ideology, there could soon be no room to argue—only death.''Minorities. Grieboski points out that the text of the draft penal code uses the word hadd (prescribed punishment), which explicitly sets death as a fixed, irrevocable punishment. He worries that it could be applied to religious and ethnic minorities like Christians, Bahais, Jews, and Azeris by treating them as apostates.Articles 225 to 227 of the draft penal code define two kinds of apostates: fetri, or an innate apostate—who has at least one Muslim parent, identifies as a Muslim after puberty, and later renounces Islam; and melli, or parental apostate—who is a non-Muslim at birth but later embraces Islam, only to renounce it again. The draft code says outright that punishment for an innate apostate is death. However, parental apostates have three days after their sentencing to recant their beliefs. If they don't, they will be executed according to their sentence. It isn't clear when this bill will be passed, though Grieboski says, "International pressure and attention—in large part due to our work—has significantly slowed the parliament's progress.''In the past, apostasy could draw a range of punishments, from imprisonment to death, under legal practices that were more ambiguous than the draft statutes. In one instance that drew international attention, Mehdi Dibaj, an Iranian convert, was held in prison for his Christian beliefs for 10 years starting in 1984. He received the death sentence at the end of 1993. But he was released from prison in January 1994 after an international publicity campaign by Haik Hovsepian Mehr, a prominent Christian pastor in Iran. A few days after Dibaj's release, Hovsepian Mehr was abducted in Tehran, and his body, with 26 stab wounds, was found secretly buried in a Muslim graveyard. Six months later, Dibaj, freed but still under a pending death sentence, was abducted and murdered...

TEHRAN, IRAN-Illyas, 20, precariously straddles two worlds.At home with his family, he's a devout Christian who wears a silver cross around his neck, devotionally reads the Bible, and, on the Sabbath, hums hymns of praise to Jesus.Easter and Christmas are celebrated with homemade grape wine, even though alcohol is banned in Iran.Publicly, though, Illyas is a devout Muslim.Before leaving home to attend university classes, he removes the cross.He falsely tells his teachers about reading the Koran regularly since, he says, expressing fealty to Islam is necessary to land a good job in Iran.And he regularly goes to Friday prayers at Tehran University, where, if necessary, he joins in chants of Marg-bar Amrika (Death to America)-although he says that he doesn't hate America and, in fact, hopes to move there someday.Illyas and his mother and stepfather-for their safety, their family name cannot be revealed—had been Muslims (as are 98% of the nation's 66 million citizens).That changed a year ago, when they were drawn to a seductively passionate voice on a satellite TV channel imploring Iranians to embrace Christianity.On hearing the voice, Illyas's mother called the channel's hotline number. She prayed with the counselor on the phone, she says, making a personal commitment to Jesus as her savior.Later, Illyas and his stepfather did the same, as the counselor from California's Iran for Christ Ministries led them in prayer.The counselor was able to put Illyas in touch with some local Iranians—also discreet believers—who could provide a copy of the Bible. "We were looking for a faith that offered the reassurance of freedom,'' says Illyas, who asked to be interviewed in a public restaurant in Tehran instead of his house.Islam is the state religion of Iran, governing most aspects of life since the 1979 Islamic revolution. But, exasperated with the obsessive atmosphere of Islamic purity in Iran since the revolution and the subsequent curbing of social freedoms, Illyas says, his family felt compelled to look for other spiritual answers, even at considerable risk.Leaving Islam for another religion, or apostasy, has long invited reprisals from the Iranian government, forcing the likes of Illyas and his family into absolute secrecy, practicing their new beliefs only in the privacy of their home. In Iran, Christians are prohibited from seeking Muslim converts, although there has been tolerance for those who are born into Christian families.The government of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has introduced legislation before the Iranian Majlis that would mandate the death penalty for apostates from Islam, a sign that it will brook no proselytizing in the country. "Life for so-called apostates in Iran has never been easy, but it could become literally impossible if Iran passes this new draft penal code," says Joseph Grieboski, the president of the Institute on Religion and Public Policy in Washington. "For anyone who dares question the regime's religious ideology, there could soon be no room to argue—only death.''Minorities. Grieboski points out that the text of the draft penal code uses the word hadd (prescribed punishment), which explicitly sets death as a fixed, irrevocable punishment. He worries that it could be applied to religious and ethnic minorities like Christians, Bahais, Jews, and Azeris by treating them as apostates.Articles 225 to 227 of the draft penal code define two kinds of apostates: fetri, or an innate apostate—who has at least one Muslim parent, identifies as a Muslim after puberty, and later renounces Islam; and melli, or parental apostate—who is a non-Muslim at birth but later embraces Islam, only to renounce it again. The draft code says outright that punishment for an innate apostate is death. However, parental apostates have three days after their sentencing to recant their beliefs. If they don't, they will be executed according to their sentence. It isn't clear when this bill will be passed, though Grieboski says, "International pressure and attention—in large part due to our work—has significantly slowed the parliament's progress.''In the past, apostasy could draw a range of punishments, from imprisonment to death, under legal practices that were more ambiguous than the draft statutes. In one instance that drew international attention, Mehdi Dibaj, an Iranian convert, was held in prison for his Christian beliefs for 10 years starting in 1984. He received the death sentence at the end of 1993. But he was released from prison in January 1994 after an international publicity campaign by Haik Hovsepian Mehr, a prominent Christian pastor in Iran. A few days after Dibaj's release, Hovsepian Mehr was abducted in Tehran, and his body, with 26 stab wounds, was found secretly buried in a Muslim graveyard. Six months later, Dibaj, freed but still under a pending death sentence, was abducted and murdered...By Anuj Chopra

To read more go to:

As in the days of Noah....

.bmp)

No comments:

Post a Comment